Not a Chore: Making Reading Purposeful

Designing Rich Reading Experiences in the Lower to Mid-Secondary Years

At a professional learning workshop, a teacher we know recently asked us these questions:

“How can we change the perception that reading is just ‘work’ amongst our students?”

“How can we get students to value reading as something they can engage with?

“How can we get them to be more active readers?”

‘Million-dollar’ questions like this come up again and again amongst us secondary teachers. They cut to the heart of the conflict between viewing reading as part of ‘doing school’ (eg: compliance, ‘because I have to’, ‘I’m being assessed on it’, 'I want to pass') and reading for purpose and pleasure (eg: “I wonder...”, “I want to learn about...”, “I’m looking for…”, “It’ll help me see it in a different way”, “I want to improve...”, etc.). What often accompanies these questions is the observation that students can often tell teachers about what they are reading or can explain the reading tasks they are doing, but struggle to articulate why they are reading in the first place. Considering that a sense of purpose shapes students’ perception of what’s worthy of their further attention and plays a crucial role in determining their ongoing commitment to learning (Goodwin, 2018: 4)., the importance of ‘why’ is paramount if we’re serious about developing rich and meaningful learning experiences in our classrooms.

This piece builds on our previous introductory post in this series, aiming to explore how a truly comprehensive approach to designing rich and diverse reading environments for students begins with establishing a strong ‘why’ for reading. More specifically, it is about shifting the perception of reading as a ‘chore’ or a shallow transaction to viewing it as a more active, intentional and meaning-making process.

More than just work: Developing authentic reasons for reading and valuing what students ‘bring to the table’

We’ve all encountered those students who, as soon as the word ‘reading’ is mentioned, tell us they ‘don’t like reading.’ Or, when given the opportunity to pick their own book to read, say that they have never finished a book or haven’t read one ‘they liked.’ These are students who see reading as ‘work’, who believe that reading is a task they must do to demonstrate or complete something, who wait for the teacher to tell them what they need to do. For these students, reading is a singular task: I am reading this text because it is what I have to do to achieve something else. This can also be the case for the avid readers we know who consume books in their own time yet find reading in class to be something entirely different. As keen readers ourselves, we’ve both experienced our own disengagement while reading some class novels as students because they weren’t books we felt connected to. In these cases, we read to answer comprehension questions or complete assessment tasks. We separated the reading we did in class from our developing reading identities.

Having students see themselves as readers who bring as much to a reading experience as the teacher opens up new opportunities for deeper engagement and enriching discussions of texts that go beyond the ‘work.’ So how can we foster authentic reasons for reading that value students’ reading identities?

Literary theorist, Louise Rosenblatt, provides a useful starting point for valuing what readers bring to texts. She writes that ‘text is just ink on a page until the reader comes along and gives it life.’ Rosenblatt’s transactional reader-response theory (1978) frames purposes for reading into two stances and asserts that most reading experiences fall somewhere between the two: the efferent and the aesthetic. Efferent reading refers to the “the cognitive, the referential, the factual, the analytic, the logical, the quantitative aspects of meaning,” while the aesthetic stance deals more with “the sensuous, the affective, the emotive, the qualitative” (Rosenblatt, 1994: 1068). An efferent stance is adopted when a student reads to prepare for another experience: when students read an article to extract specific information about a topic for a research project, when an apprentice electrician is reading a workplace safety manual to build knowledge about OHS procedures, or when television viewers evaluate electoral candidates while watching the presidential debate in preparation for an election (we realise we might be hitting a little close to home, here!). The aesthetic stance positions reading as a full emotional, intellectual and evocative experience in itself, the kind of reading where one ‘falls into’ the world of a text and ‘lives’ it. When reading, we tend to adopt a stance based on how we think the text should be read, or how we are reading it, and might move back and forth between the two. Many students see most of their reading experiences in the classroom as being purely efferent; reading instructions or finding key information to be used later on. At worst, they assume what Cheryl Hogue-Smith (2012: 59) calls the ‘deferent stance’, which involves students ‘deferring’ to the negative emotions they experience when reading difficult texts. They don’t allow themselves to ‘live’ the text or respond to the language in a personal way, nor do they draw upon their personal experiences and preferences to make meaning from the text. As teachers, we want to treat texts as stimuli for our readers, prompting closer engagement and connections. To do this, we need to value what the reader brings to the text just as much as the text itself. This ‘transaction’ creates a reciprocal relationship between reader and text.

Pat Thompson’s (2002) concept of the ‘virtual schoolbag’ is also helpful metaphor when thinking about what a student can bring to a text (if we allow them to). It’s the idea that each student brings with them diverse experiences and background knowledge to tap into which can enhance or become a jumping-off point for further learning. If we take this into account and apply it to reading, we are showing that we value what a student brings to the table, encourage them to be more aware of themselves as a reader, and support them in connecting the new to the known (by acknowledging what they already know). To build on this, the ‘Funds of Knowledge’ theory (Gonzalez, Moll and Amanti, 2005) outlines that there is great potential to improve learning from the knowledge acquired through students’ own households and communities.

We can begin to challenge the notion that reading is just ‘work’ by opening up students’ ‘virtual schoolbags’, tapping into their ‘funds of knowledge’, and acknowledging what they bring to the reading experience. As a starting point, this might include:

Activating, sharing and discussing background knowledge

Making connections to reading based on students’ own experiences

Thinking about a text’s representation of something in relation to something they have experienced or heard about (eg: is it an accurate or authentic representation?)

Reading texts in which they can see themselves

Balancing efferent and aesthetic reading stances

Encouraging students to value purposeful reading: Why ‘the why’ matters

So why does this ‘why’ matter? As Cris Tovani puts it, “A reader’s purpose affects everything about reading. It determines what’s important in the text, what is remembered and what comprehension strategy a reader uses to enhance meaning” (Tovani, 2016: 24; Pichert and Anderson, 1977). We add that it can also shape a student’s motivation to focus and persevere while reading, builds personal connections with texts and the act of reading, and can help develop self-efficacy and effort in regards to reading (Bandura, 1997; Margolis, 2014). Without purpose, students are more likely to experience their minds straying from a text, feel bored or experience disconnection from what they’re reading. They might ‘go through the motions’ and ‘say the words’ without constructing meaning from their reading. Without a clear purpose, students have no ‘game plan’ for interacting with texts and can find it difficult to separate important information from interesting details. They might find themselves highlighting anything and everything on the page, like one of us did in our first year of university when encountering increasingly challenging texts:

Without a clear reading purpose, students might struggle to distinguish important information ‘from the rest’ and can resort to highlighting ‘anything and everything’ like the example featured here.

Without being supported to determine their own reading purposes, students can come to rely on others to ‘give’ them reasons to read, developing the habits of passive readers. They might confuse genuine purposes for reading with reading assignments, like “Finish reading Chapter 6 so you can add to your character map” or “Complete ‘The Giver’ in time for the quiz on Friday.” In this case, the ‘point’ of reading becomes something that’s narrowly driven by products to be created after reading and determined by someone else other than the reader. The crucial foundations aren’t in place to approach reading as an active, personal process of meaning-making, and opportunities to develop more nuanced and original thinking are lost.

Entering a reading experience without purpose can also be likened to entering a kitchen without having any idea about what to cook. Lacking direction before being ‘let loose’ in the kitchen can produce unpredictable experiences and results. It might stop some people from even attempting to cook anything at all because it can seem too overwhelming. Others might rigidly adhere to a cookbook’s instructions and display an unwillingness to move beyond ‘the recipe’, despite their circumstances suggesting a need to adapt and be more flexible (eg: perhaps they need to cater for various dietary requirements or different palates, or for more people). On the flip side, some people might enjoy the freedom and happily experiment, feeling confident in what they are doing while drawing on their prior knowledge. An experienced chef would relish the challenge, seeing themselves as being capable of determining their own recipe. They would use their professional knowledge, experiences, utensils and ingredients intentionally and to the best of their ability, while managing to enjoy the process. So basically, without a clear purpose, the cooking process and outcome is left to chance rather than to design, which is not ideal for the chef’s kitchen OR for the classroom!

So how might we encourage students to see the ‘point’ of reading with purpose? One way to introduce this to students in an experiential way is through Cris Tovani’s ‘house’ exercise featured in her book I Read It, But I Don’t Get It (2016: 25-26), based on a passage from Pichert and Anderson (1977):

Students are given a copy of a short text titled ‘The House’ available here, and are given three different coloured pens - blue, red and green.

The teacher invites the students to quietly read the piece and with their blue pen, circle what they think is important. No further instructions are given at this point —the teacher is deliberately vague.

Students are asked to read the piece again. This time, they are asked to put themselves in the shoes of a burglar who wants to rob the house. Students are then asked to use the red pen to mark places in the text that a burglar would find important. If students need extra support to do this independently, the teacher might pause before the ‘second read’ of the text and think aloud or ask the class about what kind of information a burglar might look for, and make a list to help support them. Students might notice that having a clear purpose helps guide them in highlighting important points.

The teacher asks students to read the text for the third time. Students are asked to read it from the perspective of a homebuyer. If students need more support, the teacher can think aloud from the perspective of a homebuyer or engage the class in discussion about what a homebuyer would be looking for. In green, they are asked to mark places in the text that a homebuyer would find important.

Students share their responses and discuss why they selected particular information as the burglar’ and ‘the homebuyer’. The teacher explains that each of these people have different purposes for reading the text about the house, which helps shape what they’re looking for and how they read it.

The teacher asks students what they noticed about the three times they highlighted the piece. What was most difficult for them? What was clearer? Some students might say the first read was the hardest, because they didn’t know what they were looking for and didn’t have a clear purpose. Others might say it was hard to put themselves in the shoes of someone else while reading, and that this felt artificial. The teacher uses their answers as a springboard into discussing why reading with a clear, authentic purpose for reading is important in school and in life.

Building more active readers: Supporting students to be guided by their own ‘why’

Of course, encouraging students to see the ‘point’ in having a purpose for reading is only the beginning. The ultimate goal is to support students to determine their own ‘why’ for reading in different contexts, and to use this to take control of their reading experiences and actively guide their interactions with texts. Here are a few ideas:

‘Reading reasons’ reflection:

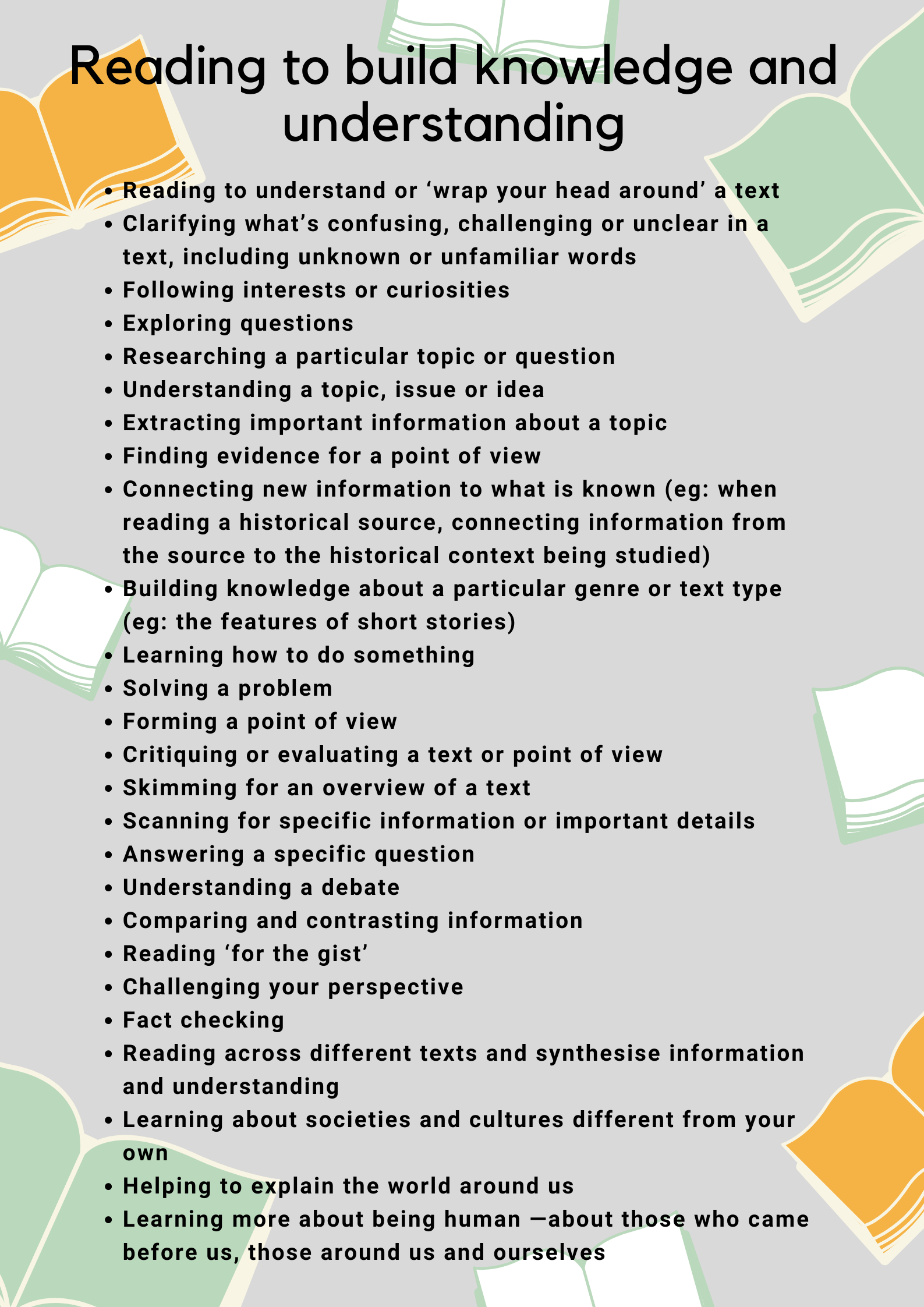

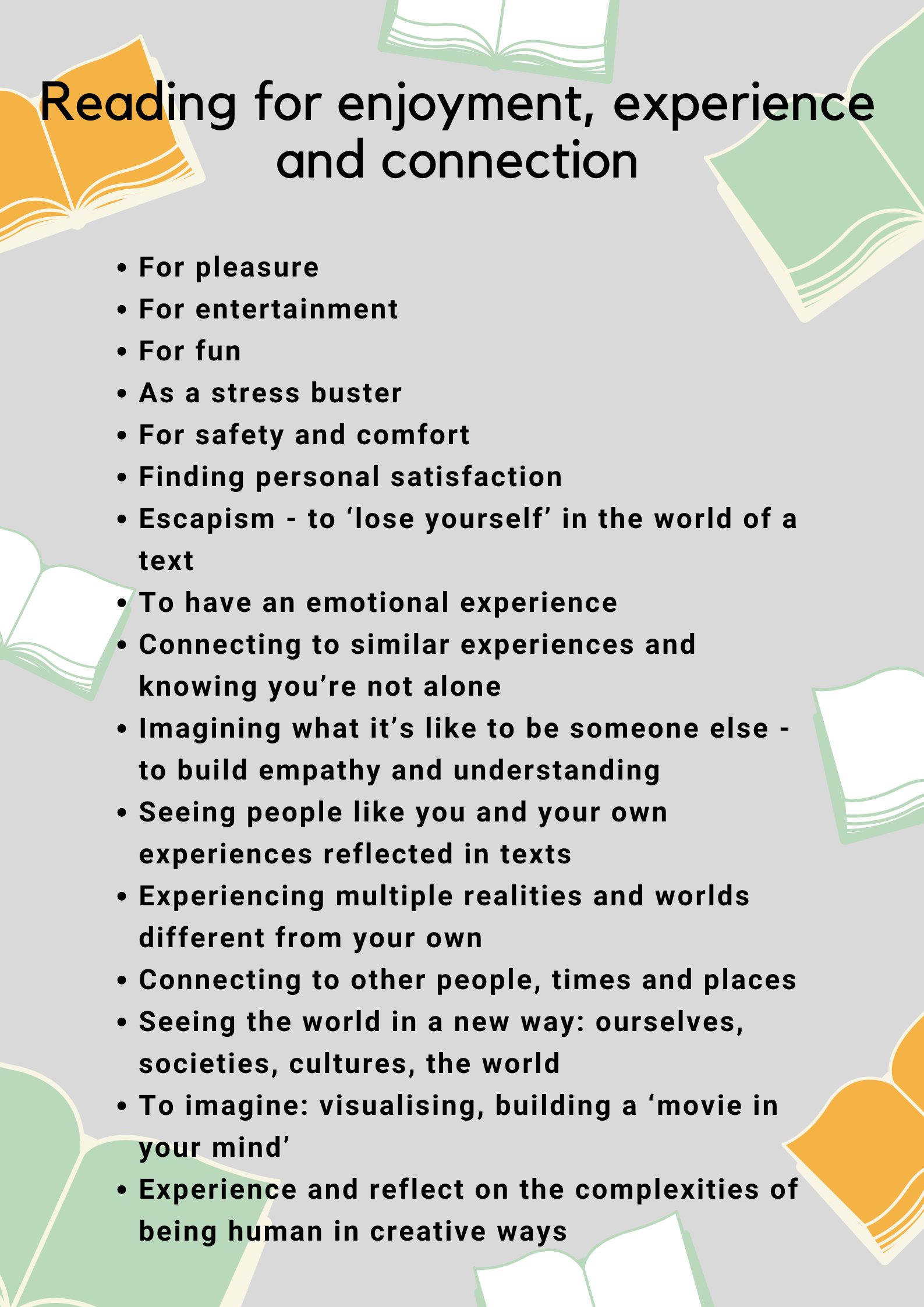

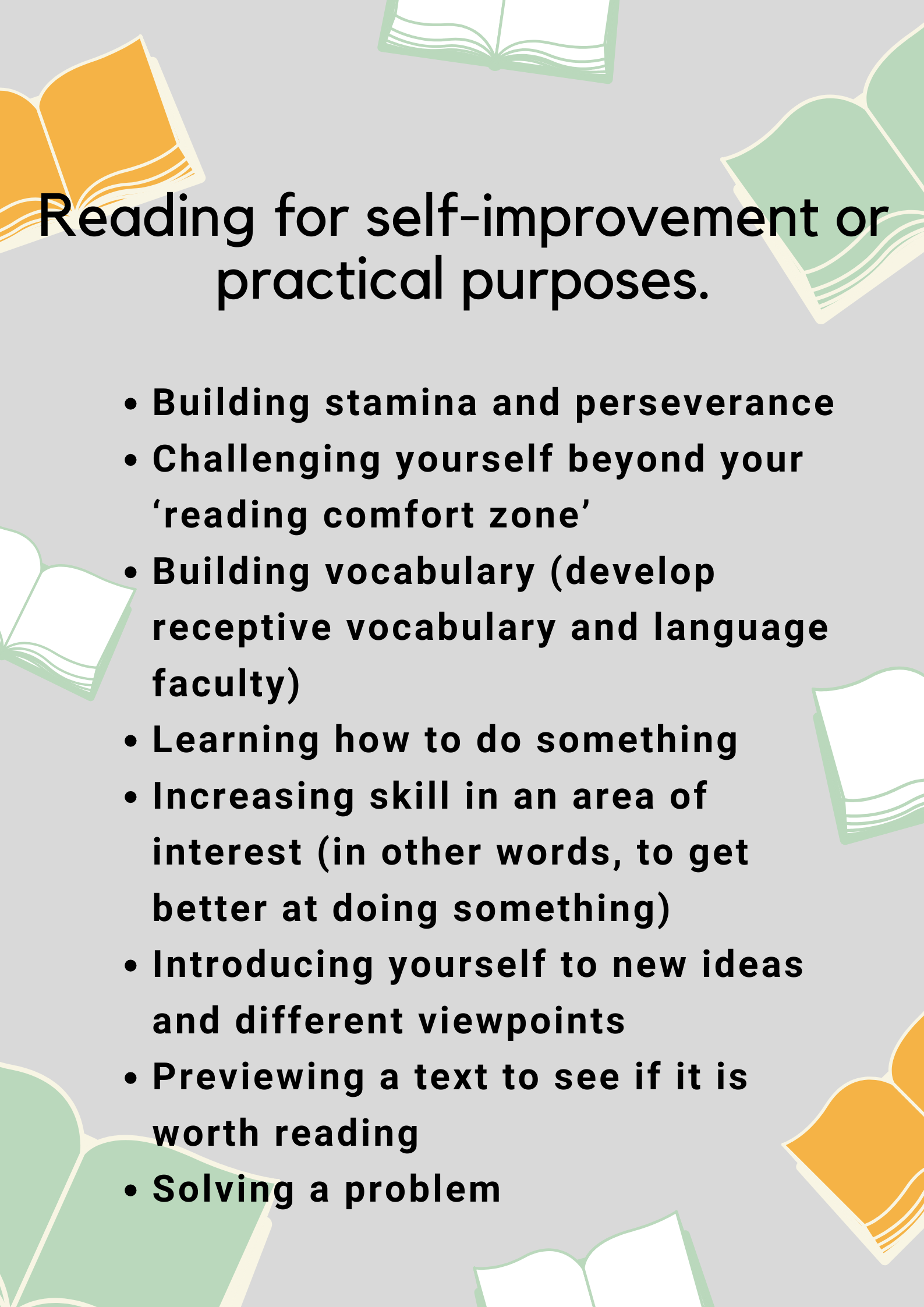

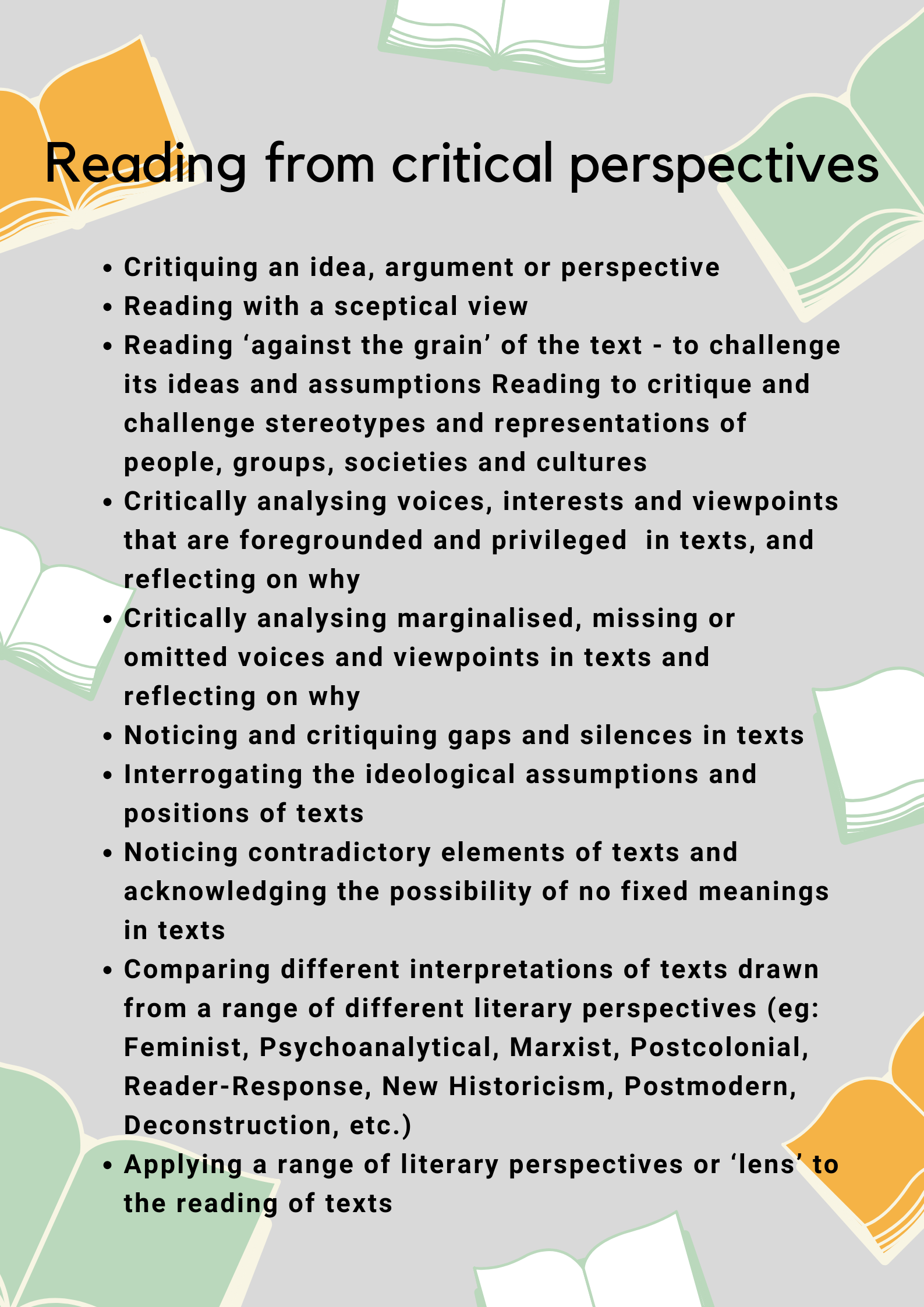

This involves presenting students with a series of reading reasons or quotes in the form of a deck of cards or a series of dot points (see the slideshows below to get some ideas for what you could add to yours). These reading reasons can either be based on a student brainstorm or you can give them a series of possible reasons from the outset. In small groups, invite students to select or highlight the reasons that represent their ‘reading comfort zones’ (i.e: the ones that feel familiar or like a habit to them) and to discuss why they made their choices. Make sure you leave some blank space so students can jot down their own purposes if they are not represented. Of these ‘comfort zone’ selections, ask them to individually select their ‘Top 3’ reading reasons and to jot them down. Next, ask students to discuss the kind of reader they’d like to be and to use their discussion and list/deck of cards as inspiration to jot down what that might look like. They can use the sentence frame “This year, I’d like to challenge myself to read for/to…” if they like. You might even make a classroom display of reading purposes (physical poster/chart or electronic graphic/slide) to refer to in future lessons.

![Quote_3[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e7985c3bf1d9e05107d09c6/1601640618750-06Z02SVYL1T7DMX03N2N/Quote_3%5B1%5D.png)

![Quote_7[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e7985c3bf1d9e05107d09c6/1601640827232-6FKZQ5XTM4O5QOF8E82S/Quote_7%5B1%5D.png)

![Quote_1[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e7985c3bf1d9e05107d09c6/1601641013215-9S22ZM9RIT1X4M35QBD4/Quote_1%5B1%5D.png)

![Quote_2[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e7985c3bf1d9e05107d09c6/1601641033015-CXV5JAYUII50KWFH52ZY/Quote_2%5B1%5D.png)

![Quote_5[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e7985c3bf1d9e05107d09c6/1601641338984-LW8YVZ16Q209FC1IG0X5/Quote_5%5B1%5D.png)

![Quote_6[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e7985c3bf1d9e05107d09c6/1601641358053-YG4TH3H0BZ09BZZGXO2M/Quote_6%5B1%5D.png)

![Quote_7[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e7985c3bf1d9e05107d09c6/1601642288330-O23JD7OGRRPG3IXWT33V/Quote_7%5B1%5D.png)

![Quote_8[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e7985c3bf1d9e05107d09c6/1601642307315-OHIE6650PJU4EEEWJZ9O/Quote_8%5B1%5D.png)

![Quote_9[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e7985c3bf1d9e05107d09c6/1601642325849-2VLJ82MUHCRMO3FH7SPV/Quote_9%5B1%5D.png)

![Quote_10[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e7985c3bf1d9e05107d09c6/1601642687127-43VBPNXISSYC5R1J8KS7/Quote_10%5B1%5D.png)

![Quote_11[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e7985c3bf1d9e05107d09c6/1601642706273-YWSA3SM40R0ZYMI44K1G/Quote_11%5B1%5D.png)

![Quote_12[1].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e7985c3bf1d9e05107d09c6/1601642726466-AB0CK8TDYIM28THK9LNO/Quote_12%5B1%5D.png)

Reading with questions in mind:

Encourage students to come up with their own questions before reading and then read to answer them. See an example of this from Stephanie Harvey’s The Comprehension Toolkit here. Alternatively, you might guide students to form overarching questions to boost engagement and focus when reading longer narrative texts or novels (eg: ‘What can [title of text] teach us about life?’ or ‘To what extent is your future already written?’ ‘Are people really in full control of their lives?’ ‘Who has the power in this story and what happens as a result?’).

Teacher modelling and demonstrating:

It’s one thing to tell a student about different reasons for reading, but it’s much more effective to show students how you determine your own reading purposes and are guided by them. As the expert readers in the room, teachers can make their thinking about this visible through a think-aloud. Reading purposes can be dependent on context, genre and the readers themselves, so it’s important to model this with a range of different texts in a variety of contexts —see this ‘Reading Reasons’ resource for some ideas. When modelling, it’s important to show how you use your reading purpose to stay motivated and monitor your own engagement and focus, or how you use it to select important information and guide your interactions with/annotations of text (eg: If I’m reading to preview a series of texts before deciding which one I’d like to read, I’d have my criteria for a ‘good book’ in mind and would jot down which books best fit that criteria. I’d also be looking for books that interest me the most). You can ‘gradually release’ students into doing this independently by asking them to practise in pairs, groups, then on their own; checking in, supporting and responding to student needs at multiple points along the way.

Ask ‘why?’:

Build the habit of asking ‘Why are we reading this?’ and co-constructing genuine reading reasons with students. You might create a class-constructed ‘Reading Reasons’ anchor chart that you add to throughout the year, and/or use a resource like this one as support. If necessary, you might ask students to follow this with the sentence ‘So this means I’m looking for…’ to further guide the process. This might work best with reading experiences that fall more towards the ‘efferent’ side of the spectrum.

‘Multiple draft’ reading:

This strategy involves asking students to read a short text multiple times (usually 3-5 times), with different purposes, before synthesising their understanding of it at the end. Elements of this strategy have been borrowed from Glen Pearsall’s ‘Three-Colour Highlighting’ strategy from The Literature Toolbox: An English Teacher’s Handbook.

Students are given different coloured pens. Eg: blue, red, green, purple and black.

’First draft’ reading: Students are asked to complete a ‘first draft’ reading of a text with a blue pen, with the purpose of identifying any parts they find confusing, challenging or unclear. The purpose here is to clarify these parts and reflect on their initial understanding. After this ‘first draft’ reading, they are asked to individually rate their understanding of the text out of ten and are invited to make a few notes about what they’ve read. Students are asked to discuss what they found confusing, challenging or unclear with a partner for a few minutes. They are welcome to ask their partner if they can help them. Student pairs share any points that remain unclear with the class and together, the teacher and students clarify these before reading further.

’Second draft’ reading: Students are asked to read the text a second time with a different purpose, using the red pen to annotate. The purpose will depend on the class’ learning goals, the learners themselves and the type of text being read. For the purposes of illustration, we’ll select this as our purpose for the ‘second draft read’: ‘Reflecting on personal connections to the text.’ Instructions to students might be: ‘Highlight any words or phrases that are moving, thought-provoking, or striking to you. Note down why they stand out to you and the connections you make when you read them.’ When students have finished this ‘second draft’ read, ask them to share their thoughts with a new partner, explaining why they chose certain parts of the text. They might want to use sentence stems like “The phrase____________ stood out to me because it makes me feel…”, “I found _____________ striking because it reminds me of…” or ‘The sentence ____________ makes me feel _______, because it connects to…’. Student pairs are invited to share and build on their thoughts with the class.

‘Third draft’ reading: Students are asked to read the text a third time with a different purpose relevant to the learning goal, students and type of text. This time, they might be asked to notice the author’s writing choices (structure, language and use of literary devices) and speculate about the effects of these choices on readers. They annotate the text with a different coloured pen and repeat the pair-share process.

’Fourth draft’ reading: Students are asked to read the text for the fourth time with a different purpose. This time for example, they might be asked to speculate about the author’s key ideas or messages. They annotate the text with a different coloured pen and repeat the pair-share process.

’Fifth draft’ reading (optional): Students are asked to read the text again, this time, being asked to see if they can notice any historical, social and cultural views and values that shape the text. Students might be asked to note what is endorsed, criticised, questioned or that which is silenced or omitted (eg: ‘What’s there?’ and ‘What’s not there?’). They annotate the text with a different coloured pen and repeat the pair-share process.

Bringing it all together: Ask students to take a ‘writing break’ to note down the most important points from the multiple readings and ‘pair-shares.’ Ask them to then rate their understanding out of ten and to compare this with their initial ‘rating.’ Invite them to reflect on how their understanding of the text shifted or deepened with each reading after adopting different reading purposes or areas of focus. Invite students to write down any questions they still have about the text, before engaging them in whole-class discussion about them, exploring how multiple readings and reading purposes can shift views and deepen understanding about texts. You might want to make the point that reading a text once is a starting point for understanding, not an end point, and that approaching each reading with intent can yield greater understanding.

‘Switching Gears’: Reading like readers, reading like writers:

This involves showing students the difference between reading for aesthetic purposes (to emotionally respond, personally connect, develop empathy, imagine experiencing the events of the story through the characters’ eyes, to visualise, etc.) and reading ‘like a writer’ (reading with ‘a writerly eye’, noticing the writer’s choices and/or conventions of a particular genre). This is a particularly useful strategy to use when reading mentor texts or in a creative writing unit, because writers learn from other writers.

This might look like presenting students with a text and engaging them in reading ‘to experience’ and personally respond to it first (eg: ‘What do you see, think, wonder?’, ‘What do you find striking, moving or thought-provoking?’, ‘What do you visualise?’, ‘What does this make you think, feel or imagine?’). Then, engage students in reading it again ‘with a writerly eye’. You might prompt them to notice any of the following that stand out to them or which appear to be ‘working’ for the writer:

Development of ideas

Organisation and structure

Word choices

Voice (including tone)

Descriptive language (related to characters, setting, events, etc.)

Figurative language

Characterisation

Dialogue

Sentence structure and fluency

Story structure

Use of language conventions

Other literary devices or genre conventions

You might follow this by asking them to consider the writing choices that inspired them the most that they would like to try in their own writing.

Teaching students to self-monitor and adjust:

Reading purposes are not static and can change when a readers’ situation changes; like if a reader comes across an unknown word, concept or phrase, or if they come across some interesting information they would like to pursue later, for example. For this reason, it is important to teach students how to self-monitor, adapt and ‘evolve’ their purposes for reading as they go, and the associated actions that might follow. This could involve using a metaphor like ‘hitting the pause button’ on their ‘main reading purpose’, and showing students how to adapt accordingly (eg: clarify unknown words in the margins, add to an ‘interesting points I’d like to research later’ list) before pressing ‘play’ again.

As readers form a habit of deliberate practice when it comes to reading with purpose, and then apply this to different texts in a variety of contexts, they set themselves up to build more background knowledge, familiarise themselves with different genres and develop metacognitive reading habits that can be transferred across disciplines and beyond the classroom.

At the end of the day...

Having a reason to read - whatever it may be - matters a lot. Knowing ‘why’ we are reading creates a strong foundation for making choices about what to read (reading material) and how to read (strategies and approaches). As Simon Sinek outlines in Find Your Why, “It is not just WHAT or HOW you do things that matters; what matters more is that WHAT and HOW you do things is consistent with your WHY.” (2017: 186).

Without digging into ‘the why’, students are more likely to adopt the habits of passive readers who view reading as something ‘happening’ to them. Instead, we want students to develop metacognitive awareness and control over their reading while valuing what they bring to their reading experiences.

At the end of the day, supporting students to develop their own purposes for reading is really about building self-aware, lifelong learners who feel empowered to make sense of the full range of reading experiences they’ll encounter in an ever-changing, information-saturated world.

References:

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Goodwin, B. (2018). Student learning that works: How brain science informs a student learning model. Denver, CO: McREL International.

Margolis, H. (2014). ‘Giving Students a Reason to Try’, Educational Leadership 72 (1). Available online: http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/sept14/vol72/num01/abstract.aspx#Giving_Students_a_Reason_toTry (Accessed 28/8/2020).

Pearsall, G. (2020). The Literature Toolbox: An English Teacher’s Handbook, Moorabbin, VIC: Hawker Brownlow.

Pichert, J.W. & Anderson, R.C. (1977). ‘Taking Different Perspectives on a Story’, Journal of Educational Psychology, 69 (4), pp. 309—315.

Rosenblatt, L. (1994). ‘The Transactional Theory of Reading and Writing’ in Theoretical Models and Processes of Reading, 4th Edition. Ruddell, R., Ruddell, MR & Singer, H. (eds). Newark, DE: International Reading Association, pp. 1057-1092.

Thomson, P. (2002). Schooling the Rustbelt Kids : Making the Difference in Changing Times. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin.

Tovani, C. (2016). I Read it But I Don’t Get it: Comprehension Strategies for Adolescent Readers. Moorabbin, VIC: Hawker Brownlow.